Last spring, I finally signed up for Foursquare, the social networking site and app that allows you to check in at places on your mobile device. When I first heard about Foursquare, I was skeptical: what’s the point, and why would I want people to know where I was at? After I decided I was going to write my dissertation on privacy and social media, I decided that it would be a good idea to play with Foursquare for a while.

At first, it was a lot of fun: I was earning badges (for example: you get a badge for checking in at a certain number of establishments in one night, and one for checking into enough different Starbucks). I was competing with friends to see who could be the mayor of certain establishments (mayorships are earned by checking in at a place the most over the last two months). It was also fun to try to get a certain place “trending,” which means that enough people are there that Foursquare would list it as trending. (This number is surprisingly small, at least in State College: 4 or 5). I also enjoyed reading tips left by other users. (my Foursquare profile)

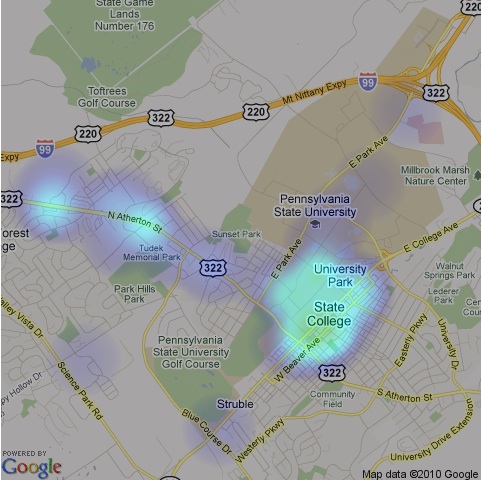

One thing I particularly enjoyed, which Robin shared back in May, is Where Do You Go, which pulls in your Foursquare check-ins and uses Google Maps to create a nifty graphic of where you frequent. Here’s mine for State College:

Pretty interesting, I suppose. But after six months or so using Foursquare, the novelty and interest has worn off. The 30 seconds I spend on each check-in seemed to just waste time, I wasn’t getting a lot out of it, and I felt that my experiment had proven complete. Fears about privacy issues (e.g., someone could rob you because they know you’re not home!) seem hyperbolic and largely unfounded (though the risks are certainly there). Largely, the whole thing is a game, as well as a marketing ploy (for businesses that offer deals for Foursquare check-ins, which probably increase the likelihood of return customers for those who use Foursquare).

The thing I found most interesting, though, is the compulsion to check-in everywhere, and the “regret” (of sorts) for forgetting to check-in somewhere. I think Foursquare says a lot more about our common compulsion to collect information about ourselves and each other than it does about privacy. And a lot of information it is: I accrued 888 check-ins over six or seven months — and this leaves out a period of time when my iPhone was broken. Users also share their check-ins on Facebook or Twitter, a convergence that I’ve noticed annoys more people than it doesn’t. (When I first started Foursquare, I accidentally had it connected to Twitter: a friend threatened to unfollow me. I’ve been tempted to unfollow people on Twitter who update with Foursquare, because unless there’s an interesting comment included, why share where you’re at?)

So yesterday, I moved my Foursquare app from the first screen of my iPhone to the last screen, and probably won’t be using it again.